Sexual violence prevention is a dynamic and evolving field. For many years, “prevention” efforts have focused on telling individuals what to do to avoid being raped. While there is some value in such strategies – commonly referred to as “risk reduction” – true prevention of sexual violence would happen long before an encounter with a perpetrator. Additionally, focusing only on what a person can do to avoid rape has led to victim blaming in our responses to survivors.The challenge in doing sexual violence prevention is a lack of evidence showing what is most effective to prevent first time perpetration and victimization. In the absence of research, practitioners focus on other resources to help inform their work. A good place to start is to understand the theoretical frameworks that guide prevention work. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have provided an overview of sexual violence prevention in Sexual Violence Prevention: Beginning the Dialogue. The CDC also has a follow-up, Continuing the Dialogue (2019)

This section includes some of these frameworks that are often relied upon to help plan for prevention activities using the best available research and resources. You can learn more about prevention framework in this section and by checking out this WCASA webinar:

- Introduction to Prevention (WCASA, 2016)

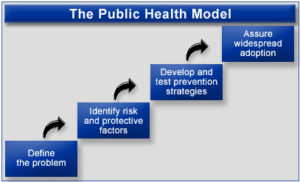

Public Health Model

Public health is a field dedicated to approaches that address the health of a population rather than one individual. Public health is a population-based approach and is one of the principles that distinguishes public health from other approaches to health-related issues. In contrast, the more common Medical Model, focuses on diagnosis and treatment of the individual.

A key reason that the public health model fits for use in the sexual violence field is that it is a community-oriented approach. Similar to efforts in the criminal justice response to put the responsibility for accountability on the community, rather than the individual survivor; the public health approach encourages the entire community to prevent sexual violence.

The public health model has been proven effective to address a wide variety of issues – including smoking and HIV – which is why this framework is being utilized for sexual violence prevention. The model is broken down in to the following steps:

- Define the problem

- Identify risk & protective factors

- Develop & test prevention strategies

- Assure widespread adoption

For more information about the public health approach to violence prevention, check out the following resources:

- The Public Health Approach to Violence Prevention (Centers for Disease Control)

- The History of Violence as a Public Health Issue (Centers for Disease Control)

- Putting Social Justice at the Heart of Public Health (PreventConnect)

Primary Prevention

Public Health and Prevention professionals define three levels of prevention: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Historically, the sexual assault movement centered much of its efforts in the secondary and tertiary levels – responding to the crisis, supporting survivors who had already been sexually assaulted, and raising awareness of available resources. Over the last decade or so, the movement has shifted toward focusing more on primary prevention or addressing the root causes of violence in order to prevent it from happening in the first place.

| PRIMARY | SECONDARY | TERTIARY |

|---|---|---|

| Before it happens | While it is happening | After it has happened |

Socio–Ecological Model & Spectrum of Prevention

Individual behavioral choices are affected by one’s own individual identity and belief systems as they relate to messages, beliefs, boundaries, and expectations expressed by significant others and other family members, parents, peer groups, school or other social community, and the culture at large.

Two models that help us understand this concept are the “social ecological model” and the “spectrum of prevention”:

Social Ecological Model

| INDIVIDUAL: Identifies biological and personal history factors that increase the likelihood of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. Some of these factors are age, education, income, substance use, or history of abuse. |

| RELATIONSHIP: Examines close relationships that may increase the risk of experiencing violence as a victim or perpetrator. A person's closest social circle-peers, partners and family members- influences their behavior and contributes to their range of experience. |

| COMMUNITY: Explores the settings, such schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods, in which social relationships occur and seeks to identify the characteristics of these setting that are associated with becoming victims of perpetrators of violence |

| SOCIETAL: Looks at the broad societal factors that help create a climate in which violence is encouraged or inhabited. These factors include social and cultural norms. that support violence as a acceptable way to resolve conflicts |

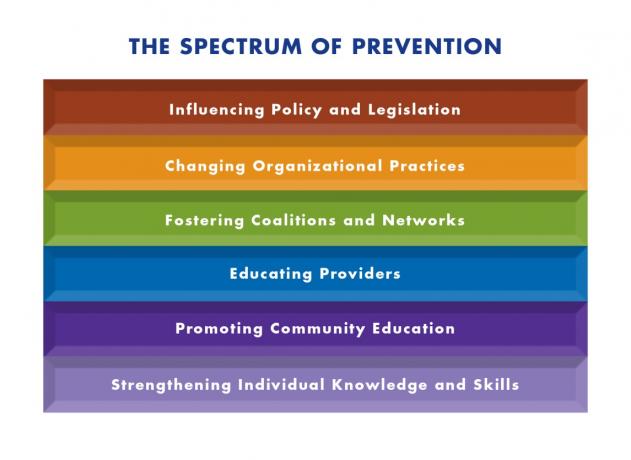

Spectrum of Prevention

| 6. | Influencing Policy and Legislation | Developing strategies to change laws and policies to influence outcomes |

| 5. | Changing Organizational Practices | Adopting regulations and shaping norms to improve health and safety |

| 4. | Fostering Coalitions and Networks | Convening groups and individuals for broader goals and greater impact |

| 3. | Educating Providers | Informing providers who will transmit skills and knowledge to others |

| 2. | Promoting Community Education | Reaching groups of people with information and resources to promote health and safety |

| 1. | Strengthening Individual Knowledge and Skills | Enhancing an individual's capability of preventing injury or illness and promoting safety |

Download a description of the spectrum of prevention (Prevention Institute)

Read more and download resources at the Prevention Institute Spectrum of Prevention page.

9 Principles of Prevention Programming

The prevention of violence can take many forms; as the field has grown, practitioners have begun to identify best practices in terms of those things that make programming most effective. The CDC has identified “9 Principles of Primary Prevention”, concepts borrowed from other prevention efforts (substance abuse, risky sexual behavior, school failure, juvenile delinquency & violence) which have proven successful in shifting people’s behavior over time. To be successful, when planning prevention programming your organization should consider the following:

| Comprehensive | Varied Teaching Methods | Sufficient Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Theory Driven | Positive Relationships | Appropriately Timed |

| Socio-Culturally Relevant | Outcome Evaluation | Well-Trained Staff |

To learn more about each of these principles, read the paper Applying the Principles of Prevention: What Do Prevention Practitioners Need to Know About What Works? (Nation, Keener, Wandersman & DuBois, 5/12/05)

You can also view the CDC’s Veto Violence project - Principles of Prevention online course

STOP SV: A Technical Package to Prevent Sexual Violence

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a Technical Package to support the implementation of sexual violence prevention in communities.

Information provided in the resources includes: This technical package represents a select group of strategies based on the best available evidence to help communities and states sharpen their focus on prevention activities with the greatest potential to reduce sexual violence (SV) and its consequences. These strategies focus on promoting social norms that protect against violence; teaching skills to prevent SV; providing opportunities, both economic and social, to empower and support girls and women; creating protective environments; and supporting victims/survivors to lessen harms. The strategies represented in this package include those with a focus on preventing SV from happening in the first place as well as approaches to lessen the immediate and long-term harms of SV. Though the evidence for SV is still developing and more research is needed, the problem of SV is too large and costly and has too many urgent consequences to wait for perfect answers. There is a compelling need for prevention now and to learn from the efforts that are undertaken. Commitment, cooperation, and leadership from numerous sectors, including public health, education, justice, health care, social services, business/labor, and government can bring about the successful implementation of this package.